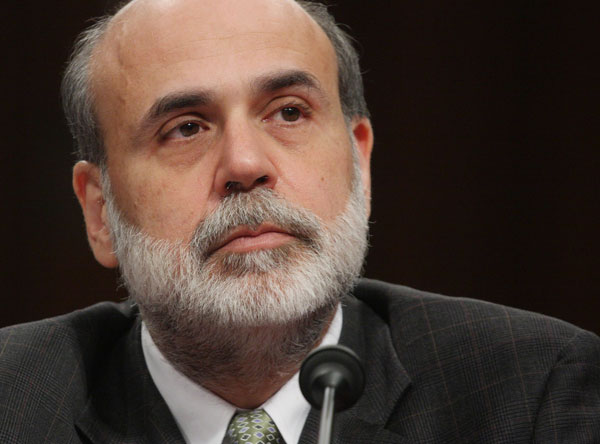

In nominating the Federal Reserve chairman to a second term, President Obama on Tuesday compared Bernanke's efforts to avert a second Great Depression to FDR's "bold, persistent experimentation" to get the country out of the first one.

But Bernanke's efforts weren't easy -- or without critics.

The Fed has taken on unprecedented risk: It took on a trillion dollars of troubled assets, slashed interest rates, bailed out financial industry titans and launched more than a dozen expensive lending programs.

Bernanke is sure to face a lively confirmation debate in the Senate before his first term is up in January of next year.

"The problem with all of the risk is that it has created an unhappiness with Congress," said Lyle Gramley, a former Fed governor. "It's going to create problems for Bernanke in his confirmation, but these things had to be done to prevent an absolute meltdown in the economy."

Exit strategy: Walking the tightrope

In part because of the Fed's aggressive efforts, there are some signs that the economy -- in free-fall late last year -- has stabilized. Gross domestic product is not falling as steeply. Neither are job losses. On Tuesday,home prices posted their first gain in three years from weak levels earlier in the year. U.S. stocks are rallying, up more than 50% in 5 months.

But all of the Fed's moves come at a cost: potential inflation down the road if the central bank is unable to rein back in the money it has pumped into the system.

Bernanke has acknowledged that concern, saying that the Fed will wind down the programs as the economy enters a recovery phase and will begin to raise interest rates.

"The fact that he had to take on a lot of risk and we have these huge debt loads shouldn't be a complete surprise -- after all, this is the Great Recession, the worst downturn we've seen since the Great Depression," said Lakshman Achuthan managing director Economic Cycle Research Institute.

"It's not about how much, it's about when they exit from this: If they leave too early, we get deep deflation, and we get spiraling inflation if they leave too late," he added. "It's a high-wire act the Fed is performing."

"Bernanke has demonstrated that he is skilled at high-drama, emergency surgery, but it's not at all clear that he is good at preventative medicine to avoid the need to visit the ER," said Achuthan. "We are all hopeful that they get the timing right, but I wouldn't bet on that heavily."

Gramley agreed that timing is everything, but argued that Bernanke is the best man for the job -- because he's the one that got us into this situation.

"Obama's nomination is not just a reward for Bernanke's past performance," said Gramley. "He is the most well-qualified person to deal with the problems that the Fed has created for itself by doing what it had to do to avoid another Great Depression."

Risky assets: Counting to a trillion

The Fed's balance sheet is a measure of the assets that the central bank holds on to. Prior to the Sept. 15 collapse of Lehman Brothers, which marked the start of the credit crisis and the point in which the recession took a turn for the worse, the Fed held less than $1 trillion in assets, most of which were in safe U.S. Treasurys.

By mid-December, the Fed's balance sheet had more than doubled to over $2.3 trillion. Many of those holdings are mortgage-backed securities -- the hard-to-value assets that brought down the financial sector.

The massive expansion began after Sept. 15, when Bernanke's Fed began rolling out lending program after lending program, sending banks cash in exchange for the risky assets.

There is a Fed program that buys up corporate debt, a program that funds foreign central banks with billions of dollars, direct purchases of mortgage-backed securities from Fannie Mae (FNM, Fortune 500) and Freddie Mac (FRE, Fortune 500), loans to AIG and ramped-up purchases of government bonds, among many others.

These initiatives have been largely successful at restoring lending among banks, and financial institutions have begun to withdraw from the programs. But the Fed is still hanging onto a majority of the assets it has taken on in the past year, and the balance sheet now stands at just under $2.1 trillion.